It’s said we live in an age of irony—irony is in; sincerity is out. It’s the importance of NOT being earnest that matters.

It’s said we live in an age of irony—irony is in; sincerity is out. It’s the importance of NOT being earnest that matters.

What is irony? Think Seinfeld—”Whatever…,” “Duh…,” “Yeah, riiiight”—all said with an arched eyebrow, a knowing wink. The “ironic stance” is detachment.

When it comes to fiction, writers, critics, and readers adore irony—most recently, Jonathan Franzen’s Corrections, Gary Shteyngart’s Absurdistan, Zadie Smith’s On Beauty, and Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones. Even classics like Pride and Prejudice are plumbed for their irony.

Jane Austen’s brand of irony derives from her subversive wit, which undercuts class structure and decorum. It’s a type of irony in vogue today: one that exposes hypocrisy and punctures holes in pretensions, beliefs and institutions that no longer stand for truth or meaning.

But literary irony is far more complex. It’s been around since Oedipus—he who unwittingly marries his mother; who searches for a king’s murderer, only to find himself; and who attains inner “sight” only when blind.

Writers from Sophoclese on down have used irony because it mimics life. Though irony takes numerous forms, the most common definition is an opposite reality from what is intended or expected: the king brought low; the underdog raised up; best-laid plans gone awry.

To learn more about irony, see LitCourse 8—based on Edith Wharton’s wonderful short story “Roman Fever.” The courses are short, free, and fun! (And that’s not ironic.)

When is a rose not a rose? When it’s a symbol. Do authors create literary symbols on purpose? Or are symbols just something English teachers invent to torment students. Could be . . . but here’s a little story.

When is a rose not a rose? When it’s a symbol. Do authors create literary symbols on purpose? Or are symbols just something English teachers invent to torment students. Could be . . . but here’s a little story.

—A Little Story—

I once wrote a poem for my English class about the beauty of a single rose. Understand when I tell you it was insipid.

But the teacher singled it out! It was, she said, a fine example of symbolism: the beauty of the single rose was how she viewed her students. In the collective we had little distinction, but individually we attained a singular beauty. Friends, I’d written a masterpiece . . . and I hadn’t a clue.

My grand inspiration had come from a cheap plastic rose stuck in my pencil holder, and I just happened to hit on the thing as my eye wandered around the room. The beauty of individualism wasn’t anywhere on the radar.

Yet that's exactly what author William J. Kennedy (Ironweed, 1983) was getting at when he wrote in a New York Times piece that the source of a writer's creativity doesn't . . .

rise up from his notepad but up from the deepest part of his unconscious, which knows everything everywhere and always: that secret archive stored in the soul at birth, enhanced by every moment of life….

—William Kennedy, “Why It Took So Long,”

New York Times, 5/20/1990

Writing is a mysterious process, and symbols often spring from the unconscious, reflecting something embedded within an author’s psyche.

In other words, that single rose of mine could just as easily have seemed lonely and forlorn. Or I might have written that its fragrance would gain potency as part of a bouquet. But it turns out I enjoy being alone or with friends one-on-one. And I avoid large groups. So perhaps even as a teen that rose had subconscious resonance.

So, no, authors don’t always intend their symbols; symbols often reflect something deep within. And readers? Our own insights into a work spring up from deep within us, as well.

If you want to learn more about symbolism—why authors use them, how they contribute to a work of fiction—take our LitCourse 9. It’s short, free, and a lot of fun.

Really, this guy's so good looking—especially if you go for wonky men with GOOD HAIR and a great pair of horned-rims. He's so… so… writer-ly.

Really, this guy's so good looking—especially if you go for wonky men with GOOD HAIR and a great pair of horned-rims. He's so… so… writer-ly.

But he can't get a break in the media, at least not on Twitter—which is where it all started.

In promoting his newest novel, Crosswords, Jonathan Franzen's publishers touted him as "THE leading writer of his generation" (caps mine).

That's a statement bound to get a reaction. And it does.

One writer quickly retweets that no matter how lauded and applauded any female author's works are, SHE "will never, ever, be called 'the greatest living American writer.'"

In that same publicity announcement, the publishers go on to tweet that Franzen, in this newest work, places the family in all its "intricacy" at the book's center. So this gets Roxanne Gay to wondering. Gay (no slouch herself, btw) tweets back asking… Hey, wait. Haven't ALL Franzen's novels centered on the family? In other words, what's the big deal about THIS one that earns him kudos as THE GREATEST WRITER? She's sort of like… ah, c'mon!

So this gets Roxanne Gay to wondering. Gay (no slouch herself, btw) tweets back asking… Hey, wait. Haven't ALL Franzen's novels centered on the family? In other words, what's the big deal about THIS one that earns him kudos as THE GREATEST WRITER? She's sort of like… ah, c'mon!

Then a guy who writes for an online journal jumps into the DUMPSTER FIRE with these choice words: "Franzen’s a good novelist. Sorry?"

But what does he even mean? Why "SORRY?" Is he sorry because he refers to Franzen as "good" but not "great"? Or is he sorry that others are resentful? Or sorry for himself? And what's with the QUESTION MARK at the end of "sorry"?

Anyway, it's all nutz. You may remember, 20 years ago, Franzen made literary headlines by dissing Oprah, who had chosen his family-centered novel, The Corrections, for her book club. But Franzen declined!! He didn't want his work given the imprimatur of a woman's book-club pick—because then…omg, MEN WOULDN'T TOUCH IT.

You may remember, 20 years ago, Franzen made literary headlines by dissing Oprah, who had chosen his family-centered novel, The Corrections, for her book club. But Franzen declined!! He didn't want his work given the imprimatur of a woman's book-club pick—because then…omg, MEN WOULDN'T TOUCH IT.

So poor Franzen, there he was, seemingly dissing both Queen Oprah AND women. Whoa! A trifecta (minus one).

Hold on—not so fast. Novelist Meg Wolitzer (no slouch either) has pointed to the same phenomenon, that men don't want to read novels about complex relationships—uh, no thanks, that's for GIRLS.

Let's be honest: Franzen's and Wolitzer's comments say more about men's sensibilities than women's. (See our jokey posts on co-ed book clubs—this one and this one, too.)

One more thing. I had the thrill of hearing Franzen in a live lecture several years back. It was essentially a master class in the ART OF WRITING. Members of the audience, many of them hopeful young writers, asked some of the sharpest, most astute questions I've yet to hear in a lecture—and Franzen was MARVELOUS. Sadly, I can't recall a single thing he said. But I do remember the hair. And his glasses. (Did I mention he's good-looking?)

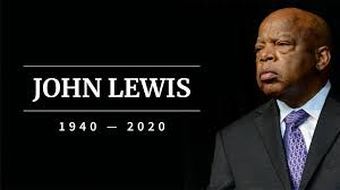

It's perhaps ironic, but surely iconic, that a GIANT of the Civil Rights Movement has died in the midst of the country's protests over George Floyd's death and ongoing racism. That "giant," of course, is U.S. Congressman John Lewis.

It's perhaps ironic, but surely iconic, that a GIANT of the Civil Rights Movement has died in the midst of the country's protests over George Floyd's death and ongoing racism. That "giant," of course, is U.S. Congressman John Lewis.

In 1998, Lewis (along with writer Michael D'Orso) penned Walking with the Wind, his memoir about growing up on the family's cotton farm in Alabama, his recollections of Jim Crow laws, and his role as a YOUNG LEADER of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

The Washington Post referred to Walking with the Wind as "the definitive account" of the Civil Rights Movement, declaring it "impossible" to read … "without being moved."

The memoir was reissued in 2015. Two years later, in 2017, Lewis's book went to the top of the bestseller charts—with Amazon announcing it had RUN OUT of new copies, while used ones were going for nearly $100.

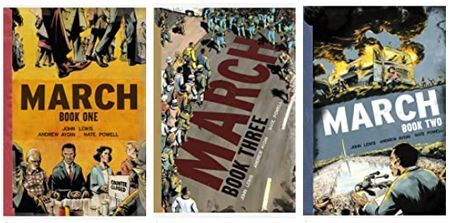

Lewis, working with two young writers/illustrators, also published March, a GRAPHIC-NOVEL TRILOGY about the Civil Rights era. The third book of the trilogy won the 2016 National Book Award.

When Book One of the trilogy came out in 2013, Lewis said this about the March project: "It's another way for somebody to understand WHAT IT WAS LIKE and … I want young children to feel it. Almost taste it. To make it real."

For book clubs that decide to tackle the RACE ISSUE, John Lewis's memoir would be an excellent place to start. Other works of note include the following titles ALSO ON LITLOVERS:

White Fragility

How to Be an Antiracist

Between the World and Me

The Hate U Give

The Warmth of Other Suns

Googling "books on racism," will turn up various lists filled with fine titles. An older one comes to mind immediately: Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? (1997), as well as THREE CLASSICS:from the 60s: Black Like Me (1960), The Autobiography of Malcom X (1964), Crisis in Black and White (1964).

Lovely words from the book editors of The New York Times—

—Letter from the Book Editors

The New York Times Book Review, April 19, 2020

♥ Thanks to my dear friend Sybil.

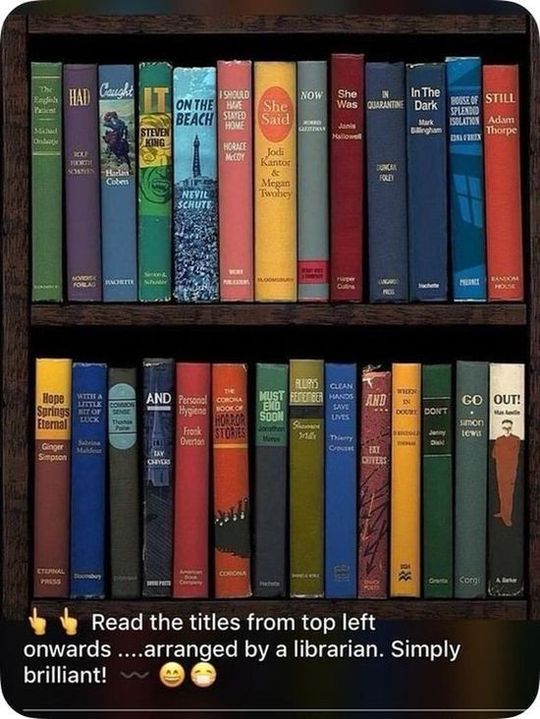

Btw... the pea-green book—bottom shelf, center—reads: "Always Remember." Even when enlarged, it's hard to read.

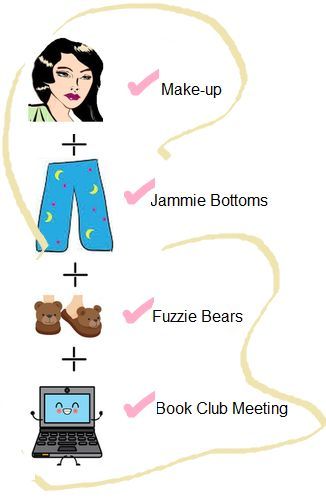

"OK … show of hands: how many of you put on MAKE-UP and a nice top—but still have on your PJ BOTTOMS?"

"OK … show of hands: how many of you put on MAKE-UP and a nice top—but still have on your PJ BOTTOMS?"

That's Mary Field opening the first ever online meeting of the VILLAGE LIT CHICKS of Lewes, Delaware.

"It seemed to break the ice," Mary told me. "Everyone LAUGHED, and off we went! A pretty good start."

The 12 members met on ZOOM, a web-based video conferencing app. All signed in without a hitch … except for one member. But her HUSBAND came to the rescue. (Try to have one of them around; that, or know where you can find a 12-year-old.)

To facilitate a sense of order, Mary assigned each member beforehand a Discussion Question for the book— Chances Are... by Richard Russo.

It worked. Conversation flowed, and "everyone was respectful—with very little talking over each other," said Mary. The meeting was such a SUCCESS that the club has planned its next for May.

One final bonus: members sent thank-you notes to Mary for her DELICIOUS New England-themed DINNER—bread bowls of clam chowder, with chilled beer and wine, topped off by a dessert of Boston Cream pie—all of which she had planned, NONE of which she had to cook. Good job, Mary!

See Meeting in the Time of Corona—Part I.

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

| Click on individual cover images. | |||||

It's a cliche to say reading is transformative. So I'll say it anyway—BOOKS permit us to lose ourselves in time and space. At the height of their powers, they even dissolve the boundary of the self.

These six books, all fairly new, offer something else: they can get you to laugh: a deep throated chuckle… all the way to a LAUGH-OUT-LOUD guffaw.

They're funny, which feels good right now, as we "shelter in place."

We're worried if not downright panicked. So, of course, GALLOWS HUMOR is on the rise—proof once again that humans will always find a way to laugh in dire times.

Please allow me a DISCLAIMER:

Many find humor tasteless right now—especially if they've taken ill or know someone who has. But laughter is in no way meant to denigrate the seriousness of the virus or make light of how precarious life has become.

Neuroscience tells us that laughing has a BENEFICIAL affect, triggering the release of endorphins, our brain's natural mood elevator, and suppressing cortisol, a stress inducing hormone.

Above are a few memes that have popped up in my texts and emails, brightening my day.* So please, find HUMOR, share a LAUGH, and feel KINSHIP. We're in this together.

♥ Thanks to my sister, Janet, who always keeps me laughing.

We're all into social distancing, right? And scrubbing hands while singing "Happy Birthday" (twice, yes?).

We're all into social distancing, right? And scrubbing hands while singing "Happy Birthday" (twice, yes?).

Book clubs are affected by the VIRUS, of course. So if you haven't canceled future book club meeting(s), you may be doing so soon.

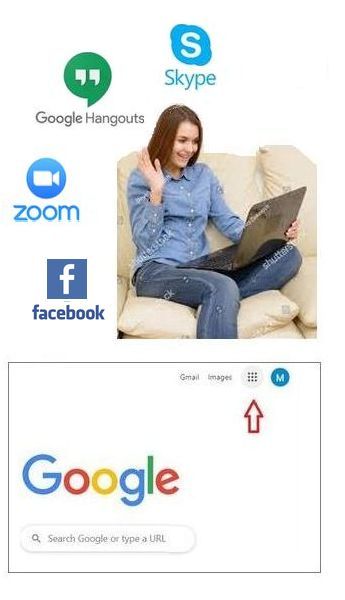

But don't give up. You can still meet using group VIDEO MEETINGS via Skype, Google Hangout, or Zoom. *

The apps are FREE … and will accommodate up to TEN PEOPLE. Zoom will handle more, but limits you to 40 minutes. All are fairly easy to set up.

Follow the app's instructions. If you run into trouble try site Support or Help … or reach out to an 11-year-old (after all, they're not in school).

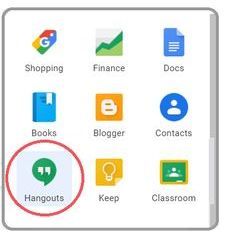

♦ GOOGLE HANGOUT (see photos)

1. Go to Google's home page

2. Click on the app in the top right corner.

3. Scroll down the menu till you find "Hangout."

4. Click on the icon to open it up.

♦ SKYPE (click on links below)

1. Go directly to Skype to download the app.

2. Watch this intro video at Tech Boomers. It's not great, but it's better than others.

♦ ZOOM

1. Go directly to Zoom to download the app.

2. Watch this intro video on YouTube. It's pretty thorough.

And there's always Facebook. Facebook launched its video chat in late 2016, but it's limited to 6 PEOPLE at a time (although more can listen in). If you've already set up a private a Facebook GROUP, click on the "video" icon in the upper-right-hand corner to join an ongoing chat or start a new one.

Whatever you decide, dear readers, STAY WELL—and that goes for your families and friends, as well.

See Meeting in the Time of Corona—Part 2

♥ Thanks to my daughter, who's younger than I am… and smarter. This post was at her suggestion.