What's an ancient German tribe have in common with medieval church architecture?

What's an ancient German tribe have in common with medieval church architecture?

And what do flying buttresses have to do with horror fiction?

Finally, what's any of it got to do with black lipstick and body piercing?

Goth. Gothic. What do those terms mean, and how are they related? So let's find out.

The 1st piece of the puzzle starts with the GOTHS, a Germanic tribe mentioned by the Greeks way back in the 4th century B.C. We know them, of course, as the group that sacked Rome 700 years later, in 410 A.D.

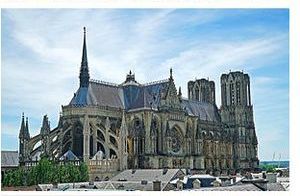

For the 2nd clue, skip ahead to the 11th and 12th centuries, long after the fall of Rome, when a new form of architecture — featuring pointed arches, vaulted ceilings, and flying buttresses — sprung up in Western Europe. That design led to the great medieval castles and cathedrals.  Although today we refer to the style as GOTHIC, at the time it was called "French Work" because of its origin in France.

Although today we refer to the style as GOTHIC, at the time it was called "French Work" because of its origin in France.

But now jump to 1453 and the fall of the eastern remnant of the Roman Empire to the Ottomans. Driven out by the collapse of Constantinople, Greek scholars fled to the West, carrying with them the writings of the ancient Greeks and Romans.

Widely read throughout Europe, the classical writings were a revelation, sparking a rebirth — which we now call the Renaissance — in all branches of culture, including architecture. The classical Greco-Roman style, with its columns and domes and elegant proportions, became all the rage.

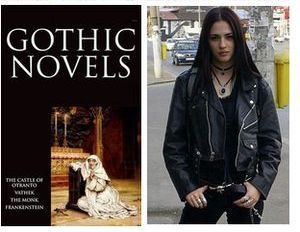

What about those glorious cathedrals and castles? Not so glorious. Seen as old and fusty, they came to be associated with a dark, barbarous past. From "barbarous" it was a short leap in imagination and linguistics to the "barbarians" who destroyed the classical world of Rome — the Goths. So that's how we got to GOTHIC architecture. The 3rd clue takes us to 1764, when Horace Walpole published The Castle of Otranto: A Gothic Story. The novel — set in a dark, foreboding castle, complete with dungeons, secret pathways, mysterious supernatural elements, and a damsel in distress — was wildly successful, spawning an all new horror genre.

The 3rd clue takes us to 1764, when Horace Walpole published The Castle of Otranto: A Gothic Story. The novel — set in a dark, foreboding castle, complete with dungeons, secret pathways, mysterious supernatural elements, and a damsel in distress — was wildly successful, spawning an all new horror genre.

Over the years, similar types of works followed: Frankenstein, Hunchback of Notre Dame, Dracula, Fall of the House of Usher, and Phantom of the Opera are among the best known. All feature dark eerie settings — sinister castles, abbeys, monasteries, or old manses — that brought to mind the heavy, medieval architecture by then known as Gothic. And so we arrive at the GOTHIC novel.

Gradually, the emphasis of Gothic fiction shifted away from the dreary settings to the creatures at the heart of the stories — monsters, ghosts, ghouls, and vampires — or to the dark, brooding, sometimes villainous, human characters.

The 4th and final piece of the puzzle came in 1979, the year the post-punk band Bauhaus released "Bela Lugoi's Dead." The song refers to the 1931 film Dracula and its Hungarian star, Bela Lugosi. Bauhaus and other post-punk bands are credited with inspiring an underground cultural aesthetic — black clothing, nails, lips, and eyeliner — reminiscent of Gothic fiction. It's GOTH, man.

So here we are: we've gone from the GOTHS to GOTHIC to GOTHIC to GOTH. And it took only 2,300 years.

NEXT UP? We'll talk about the Gothic novel in the 21st Century. Stay tuned.

Interpreting literature can be boorish business; just skim book reviews in major dailies—or customer reviews on Amazon. Even book clubs can work themselves into a lather over different ways of reading the same words.

Interpreting literature can be boorish business; just skim book reviews in major dailies—or customer reviews on Amazon. Even book clubs can work themselves into a lather over different ways of reading the same words.

Yet if we learned anything from Post Modernism, it's that words don't confine themselves to a single meaning … which is why it was so gratifying to come across this comment by Margaret Atwood.

I’m not comfortable giving interpretations of my work. If I were to provide one, it would become the definitive interpretation, inhibiting readers from finding their own meanings.

Talk about humility. Atwood acknowledges that while an author may exert full authority over plot and characters, she has no such control over her readers.

Readers should feel free, she seems to suggest, to derive meanings, separate from hers. That would imply separate from other readers, too—all of whose ideas may be equally valid.

Words of caution. The operative word in the above sentence is "may"—other interpretations may be equally valid—which means we're not free to go off the reservation and shoot at anything that moves. Interpretations need to be supported by evidence within the text and consistent with the general sense of the work.

In other words, Robert Frost's "Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening" is pretty much NOT about Santa Claus. (I had a student once who insisted it was—mistaking a literary parody for the real thing.)

Do mysteries and thrillers make good book club reads? More important, do they lead to good discussions?

Do mysteries and thrillers make good book club reads? More important, do they lead to good discussions?

Take a stroll through any bestseller list; you'll find thrillers and detective stories at (or near) the top. I love suspense mysteries (love them)! But here's my suggestion—read them on your own time. They don't necessarily inspire great book club discussions, primarily because characters are short on development...and plot discussion boils down to "what did you know and when did you know it?"

There are, of course, exceptions. A number of recent authors have jumped the genre ... moving the mystery/crime thriller into "literary fiction." What's that mean?

When critics talk like that about a crime thriller—specifically the new Gillian Flynn Gone Girl...or Tana French's Broken Harbor—they're talking about wonderful, often witty, prose; solid character development; and the exploration of philosophical ideas. Kate Atkinson is another writer who's moved the genre into high literary gear.

The three—Flynn, French, and Atkinson—are not only terrific suspense writers...they've been singled out as writers who probe deeply into character, motivation, how the past impinges on the present, and the nature of good and evil. They get us to ponder our own relationships, as well as the untenable choices life sometimes gives us. In other words, they make us think...and thinking always makes for good book conversations!

On top of good writing, two other requirements exist for great mystery/thrillers:

- The author must let the line out slowly, knowing precisely when to withhold—and when to release—information. It's a plot technique known as "suspended revelation,"—mysteries depend on it; in fact, it's their defining characteristic. (See LitCourse 6 on Plot.)

- The clues should be buried in plain sight—yet so cleverly that the reader won't pick up on them. Great mysteries stand up to a re-read, which only then reveals how, when, and where the author hid the clues.

If neither of those conditions is met, the story turns predictable, losing the element of surprise—the very thing that makes mysteries and thrillers so satisfying.

You've seen the cartoons in which characters say one thing—but they're thinking another. Authorial intention is sort of like that.

Contemporary literary theory pretty much debunks the idea that authors say exactly what they mean—because the words on the page don't always support their intended meaning. Or readers find additional meanings that authors hadn't considered.

Here's an interview with Peter Carey*, author of Parrot and Olivier in America and Oscar and Lucinda. An audience member asked Carey about an episode in the latter novel that reminded her of Adam tasting the FORBIDDEN FRUIT.

Here’s Carey’s response:

Your way of reading holds up perfectly, I think, and it’s totally consistent with the book and consistent with my intention, and yet it never occurred to me.

Then he said …

So isn’ t that the extraordinary thing about literature? It only really works when the reader reads it because until then…it’s words on a page…. Everybody brings their own lives, and their own experience, their own intellect… and then a book is made! And that’s the wonder of literature.

No one could have put it better. You can listen to the full interview from this 2003 BBC World Book Club broadcast.

* Carey, by the way, is a double MAN-BOOKER Prize winner. Yes, he won two times—for Oscar and Lucinda (1988) and for True History of the Kelly Gang (2000). (J.M. Coetzee and Hilary Mantel are the only others to win twice.)

Olive Kitteridge got me thinking about point of view—who gets to tell the story. Elizabeth Strout’s book shifts from character to character, a narrative technique that lends her work its depth and beauty.

Olive Kitteridge got me thinking about point of view—who gets to tell the story. Elizabeth Strout’s book shifts from character to character, a narrative technique that lends her work its depth and beauty.

We see Olive, not only as she sees herself, but as she’s seen by the community. The pay-off is a richer, far more complicated portrait of Olive than if she alone—or any single narrator—had told us the story.

Point of view, or perspective, is one of the most important decisions an author has to make. Whoever tells the story shapes the story.

A little game: take a couple of novels, change the narrators…and see what happens. Try this as a book club activity. Here are some ideas to get started:

- Remains of the Day: what if Miss Kenton told the story rather than the butler Stevens? We’d miss the rich irony of a hopelessly naive narrator. In fact, if we weren’t inside Stevens’s head, he would seem a pitiless monster of a being.

- Gilead: if we were to see the story through shifty, unreliable Jack Boughton, the story’s prodigal son, we would never experience our own sense shame as we, along with Reverend Ames, willfully pass judgment on a misunderstood character.

More on point of view at a later date. In the meantime take our free LitCourse 8 on Point of View. It’s fun…quick…and informative.