Blogging & Musing

It was hard not to notice the number of recent books with birds on the cover. So I made a brief little survey of book covers just for fun.*

Pause over the cover mage to see title and author; click for a link to our Reading Guide or Amazon (if we don't have a guide).

Feeling guilty about all the reading you do ... and all the chores you DON'T do? Relax. It turns out you're a finer person for keeping your nose in a book. So keep reading.

Feeling guilty about all the reading you do ... and all the chores you DON'T do? Relax. It turns out you're a finer person for keeping your nose in a book. So keep reading.A new study shows that books enable us live up to our better selves. The researchers, Emanuele Castano and David Comer Kidd, found that people gain empathy and social intelligence after reading certain kinds of books.

What kind of books? Well, not the blockbuster kind. So nix the heart-thomping thrillers or the steamy romances. The study refers specifically to "literary fiction"—well-developed characters and storylines that explore complicated human relationships—the very kind of books we read in book clubs.

One of the books used in the study was Round House by Louise Erdrich, which (at the time of this writing) happens to be the 3rd most requested book on LitLovers. (See our Popular Books page.)

One of the books used in the study was Round House by Louise Erdrich, which (at the time of this writing) happens to be the 3rd most requested book on LitLovers. (See our Popular Books page.)There's a reason why books like Round House matter. According to the New York Timesarticle:

[L]iterary fiction leaves more to the imagination, encouraging readers to make inferences about characters and be sensitive to emotional nuance and complexity.

You can read the full story in the NY Times HERE. It's fascinating and well worth the time.For Book Clubs: Consider taking time during one of your meetings to talk about the books that have altered the way you perceive people and the world around you. Which books have enlarged your ideas about life and your role in it?

Mention worthy: Publishers Weekly (PW) posed a question to Claire Messud in a recent interview that roused a remarkable response. So remarkable, it's worth reporting on here.

Mention worthy: Publishers Weekly (PW) posed a question to Claire Messud in a recent interview that roused a remarkable response. So remarkable, it's worth reporting on here.

The question concerned the heroine in Messud's new book, The Woman Upstairs.

PW said: "I wouldn’t want to be friends with Nora, would you? Her outlook is almost unbearably grim."

Messud Responds . . .

For heaven’s sake, what kind of question is that? Would you want to be friends with Humbert Humbert?

Would you want to be friends with Mickey Sabbath?

...Saleem Sinai?

...Hamlet?

...Krapp?

...Oedipus?

...Oscar Wao?

...Antigone?

...Raskolnikov?

...Any of the characters in The Corrections?

...Any of the characters in Infinite Jest?

...Any of the characters in anything Pynchon has ever written?

...Or Martin Amis?

...Or Orhan Pamuk?

...Or Alice Munro, for that matter?"

If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble. We read to find life, in all its possibilities. The relevant question isn’t “is this a potential friend for me?” but “is this character alive?"

Don't Mess with Messud!—was how PW responded to Messud's response. It's comment had clearly "rankled" the author, PW admitted, BUT...it gave Messud a chance to "show her chops. We're so glad we had that conversation," ended PW graciously.

Messud is the author of the 2006 The Emperor's Children (see reading guide here; see LitLovers review here), as well as this most recent 2013 novel, The Woman Upstairs.

For book clubs to consider:

1. Do we read to find friends?

2. How important is it to like the characters in the books?

3. Do we feel let down when we dislike them?

4. Talk about some of the books you've read and whether or not your enjoyment of them—or disappointment in them—had to do with the likability of the characters.

Book marketers have given in...or smartened up. Either way, they've taken a page from the movie folks and now create film trailers to promote new books. Some of the trailers are pretty ho-hum. But we've found a couple that are ho-ho-hilarious. Really funny.

Book marketers have given in...or smartened up. Either way, they've taken a page from the movie folks and now create film trailers to promote new books. Some of the trailers are pretty ho-hum. But we've found a couple that are ho-ho-hilarious. Really funny.

The first is Teddy Wayne's The Love Song of Jonny Valentine. Wayne is a wonderful comic writer, a terrific satirist, who in this book sets his sights on the commercialization of an 11-year-old rock star sensation, a la Justin Bieber. A child prodigy, Jonny is there for the taking: his life is commodified by just about everyone, including his own mother.

Here's the Video Trailer.

Here's our Reading Guide.

Second up, is John Kenney's novel Truth in Advertising. Again, like Teddy Wayne's, this is a comic novel: a sardonic take on the advertising world of New York. Finbar Dolan, the book's hero (not a River Elf), carries around a lot of angst—about the job, his family, and his love life. He sweats the big stuff.

Here's the Video Trailer.

Here's our Reading Guide.

Have fun with these. The more you watch them, the funnier they are. If your book's trailer is any good, play it at the book club meeting—it's a great way to break off socializing and signal the beginning of the discussion.

I've written twice* before about what's to become of libraries in the digital age. A widely emailed New York Times article should give heart to all of us who have worried about their fate. Here's the gist...

I've written twice* before about what's to become of libraries in the digital age. A widely emailed New York Times article should give heart to all of us who have worried about their fate. Here's the gist...A Pew Survey found recently that the percentage of those who believe book borrowing is a "very important" library service (80%) is about the same as those who believe computer access is a "very important" library service (77%). As it happens, libraries have been meeting the challenge of the digital age all along:

In the past generation, public libraries have reinvented themselves to become technology hubs in order to help their communities access information in all its new form.It's possible to have too much information. Back in the dark ages, when the web was in its infancy, a friend of mine quipped that it needed a good librarian to get the stuff organized. This was a few years before Google. Today, the web clocks in at nearly 15 billion web pages, and it's still growing at a mind-boggling rate. Google or no Google, we have digital overload.

—Kathryn Zickuhr, Pew Research Center

All of which makes an "information manager" more important than ever—specialists who know how to search, locate, categorize, and vet information. And guess who does that really, really well? Librarians.

What's more, librarians share their skills. Every major library now offers its patrons—not just access to digital equipment—but courses in how to use it...and how to maneuver the vast information galaxy.

So 100 years from now, even if we find their shelves bereft of the printed book, libraries and librarians will be more important than ever—as communal centers of knowledge. We'll still need them—so we better damn well make sure they're around! A warning to us all: we need to keep a close watch on our municipal budgets.

* See Whither Go Libraries in the Digital Age—Part 1 and Part 2.

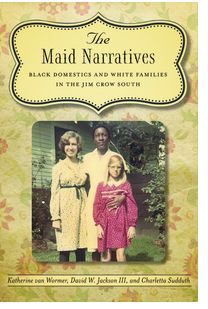

Art imitating life ... imitating art. A new nonfiction book by three academics gives credence to The Help, Kathryn Stockett's novel of black domestics in white families during the South's Jim Crow era.

Art imitating life ... imitating art. A new nonfiction book by three academics gives credence to The Help, Kathryn Stockett's novel of black domestics in white families during the South's Jim Crow era.

The real maids interviewed for The Maid Narratives encountered much the same treatment we all read about in the fictional version—separate entrances, toilet facilities, and dining areas.

Yet co-author Katherine van Wormer found much that surprised her: stories that were more positive than expected, a sense of forgiveness, and lack of bitterness.

A few deep bonds were forged between black maids and their white employers. "Love can cross over color-lines," says co-author Charletta Sudduth, whose own mother was a domestic and interviewed for the book:

I think that a lot of women—black and white women—shared a relationship that was genuine and true. They found ways to help each other, found ways to cry with each other, found ways to laugh.Nonetheless, it was still a one-way racial street. As co-author van Wormer points out:

The whites thought of the maids as members of the family. The blacks didn’t see it that way. They had their own families, and the white people didn’t pay any attention to that.The Maid Narratives was in research stage when The Help came out. Rather than feeling dismay at having been beaten to the punch, the book's authors saw only benefits. The huge publicity surrounding Stockett's best seller convinced many former maids to come forward and tell their own stories.

"For many of the women," says third co-author David Jackson, "this was the first time they could talk about it and begin to heal. It was therapeutic."

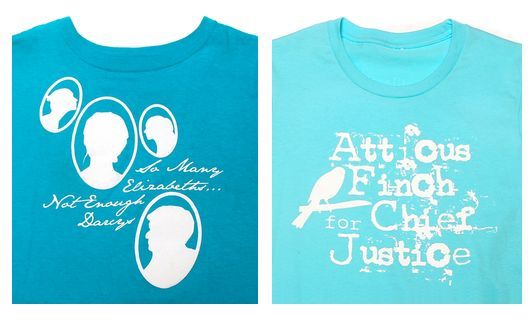

Take a look at these cool t-shirts by Classic Coup, a literacy project started by devoted teacher and avid reader, Cindy McCain in Nashville. For Each T-shirt sold, money is donated to schools and orphanages in Ecuador, where Cindy taught this past summer (2012).

Take a look at these cool t-shirts by Classic Coup, a literacy project started by devoted teacher and avid reader, Cindy McCain in Nashville. For Each T-shirt sold, money is donated to schools and orphanages in Ecuador, where Cindy taught this past summer (2012).Lots more where these come from. So head over to her Classic Coup Blog and her Classic Coup Store...and buy t-shirts for all your kids, grandkids, nieces and nephews. Spend some time learning more about what she and her students are doing to make the world a better place for those who need it most.

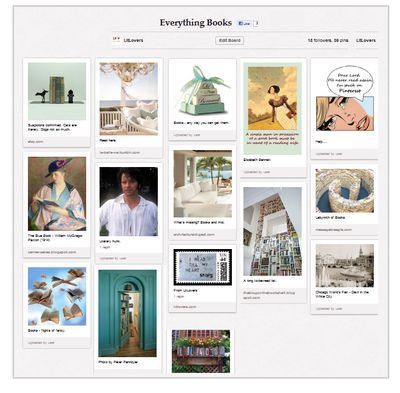

One more addiction—this one's not on a plate or in a bottle but online. Pinterest: more fun than any one person should be allowed to have, but it's a great tool for book clubs. Move over, Facebook.

One more addiction—this one's not on a plate or in a bottle but online. Pinterest: more fun than any one person should be allowed to have, but it's a great tool for book clubs. Move over, Facebook.Pinterest is a social media site—it's an online "bulletin board" where you "pin" your favorite images from anywhere on the web, especially from other Pinterest users. Or you can pin images and photos you've already downloaded onto your computer. Pinterest does all the formatting for you. It's simple easy and devilishly clever.

Below is what a "bulletin board" looks like—a snapshot of LitLovers' board on Pinterest. Be sure to visit our real page—"Everthing Books" — to see the complete board. The Pinterest button on LitLovers home page (left-hand colum) will also take you there.

Why would book clubs use Pinterest? Because it's a great way to keep everyone up-to-date and to maintain a visual record of club activities. Your club can have its own page—and you can have as many "bulletin boards" on your club page as you want. You can add everything related to your book club...

- Add a "bulletin board" for the books you're reading—there's a space for captions (say, for titles or meeting date and locale).

- Add comments about each book. Any member can comment; it's just like Facebook.

- Add as many boards as you want—on the same page. Add a 2nd board for potential book ideas, a 3rd for club photos, and 4th for book-related recipes. Anything.

- Add boards for every member—on the same Pinterest page as your book club. Members can use their individual boards to "pin" everything...from the books they're reading on their own, to book-related gifts or personal photos.

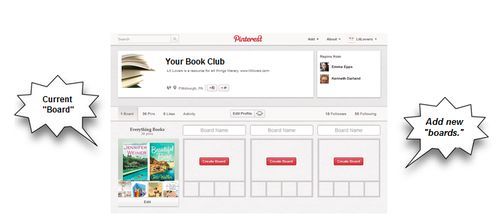

Take a look at a snapshot of a standard Pinterest page. You click on the empty gray boxes to add a new "bulletin board" and a title for your board. Then pin away.

It looks more complicated than it is. Believe me... if I can do it, you can do it. Head to the Pinterest Help page to get started. You'll find it under "About" in the upper-right corner. Follow the directions as best you can*...and "pin" to your heart's content.

Be warned, however. Once you get on Pinterest, you'll complsively click all over the place. You may not be able to get off.

* Call on a young person if you get stuck. They know everything.

Today's open letter from the American Library Association could have been a warning shot across the bow of U.S. publishers. But that's presuming the ALA could actually make good on its warning...which it can't. Libraries don't even have slingshots to use against publishing Goliaths.

Today's open letter from the American Library Association could have been a warning shot across the bow of U.S. publishers. But that's presuming the ALA could actually make good on its warning...which it can't. Libraries don't even have slingshots to use against publishing Goliaths.Still, it's a smart move—using an open letter to turn the spotlight on three of the country's (world's) largest publishers, who refuse to sell ebooks to libraries. The ALA's letter puts it this way...

Simon & Schuster, Macmillan, and Penguin have been denying access to their ebooks for our nation’s 112,000 libraries and roughly 169 million public library users.... The Glass Castle [ebook is] not available in libraries because libraries cannot purchase [it] at any price. Today’s teens also will not find the digital copy of Judy Blume’s seminal Forever, nor today’s blockbuster Hunger Games series —September 24, 2012

Not all publishers refuse to sell to libraries, as the ALA points out. However, without those three major players, ...

If our libraries’ digital bookshelves mirrored the New York Times fiction bestseller list, we would be missing half of our collection any given week due to these publishers’ policies. [ALA's emphasis.]This week, however, publishers and the ALA are meeting to try to iron out their differences—a hopeful sign, given that talks back in January of this year (2012) reached a stalemate...or worse. Penguin pulled out of library ebook sales altogether.

Random House, on the other hand, stuck around...but nearly tripled its prices to libraries, and Hachette's will more than double. HarperCollins limits libraries to lending its e-books only 26 times. This is according to Publishers Weekly.

But it's not like publishers are the bad guys. They are businesses...and must make money to survive. So stay tuned for another exciting installment in our suspense series—Libraries in the Digital Age.

See both Whither Go Libraries in the Digital Age articles—Part 1 and Part 3

Joshua Henkin is one of my favorite writers: his 2008 novel, Matrimony, was chosen as a NY Times Notable Book and reviewed here four years ago. His newest novel, The World Without You (2012) has received stellar reviews—phrases like "subtle and ingenious," "blazingly alive...a living, breathing world," "powerful and unexpected...compassionate and beguiling." See LitLovers Book Review.

Joshua Henkin is one of my favorite writers: his 2008 novel, Matrimony, was chosen as a NY Times Notable Book and reviewed here four years ago. His newest novel, The World Without You (2012) has received stellar reviews—phrases like "subtle and ingenious," "blazingly alive...a living, breathing world," "powerful and unexpected...compassionate and beguiling." See LitLovers Book Review.From my keyboard to your eyes—READ THIS BOOK! It's the story of a family that gathers a year after their son and brother Leo was kidnapped and killed in Iraq. Parents, siblings, and Leo's widow meet in remembrance and grief...as they struggle to live in a world without him.

Joshua has generously "stopped by" to answer some questions about his newest novel, and LitLovers is delighted to welcome him.

Q Not a lot happens in The World Without You in terms of plot—though a good deal does happen among characters. You seem to prefer character-driven over plot-driven stories. Why is that?

You’re not the first person to say that not a lot happens in The World Without You in terms of plot, and while I understand what you’re saying, I disagree. A son has been killed in the Iraq War. His parents are splitting up from the grief. His widow has a new boyfriend. There’s a lot of plot there.

That said, I think you’re fundamentally right, in that my fiction is always less concerned with what happens than with the characters who act and are acted upon. I think plot is important for fiction (you are, after all, telling a story, and a writer should never forget that), but the greatest plot in the world won’t be of interest to the reader if the characters don’t come alive on the page.

To me, fiction is first and foremost about characters. I want my readers to feel at the end of my book that they know my characters as well as or better than they know the people in their own lives. If I’ve done that, then I’ve succeeded.

Q The characters in The World Without You are beautifully realized—each clearly delineated from the others. How do you invent them—all the grainy details of their personalities and behavior? Do you find yourself, say, brushing your teeth...when an idea jumps out at you? Do you deliberate? Do you hold conversations with them? Do the characters ever take over? How does the miracle occur?

The miracle occurs slowly over time. You live with your characters day in and day out for years, and eventually they come to be fully formed. Who is your character? the writer should ask. Where did she grow up? What kind of work does she do? Does she like spinach? Does she sleep on her back, her stomach, or her side? It may seem inconsequential to know (much less describe) how a character sleeps, but not if the gesture is laden with meaning, as all gestures in fiction should be. Does the character who sleeps on her side do so because she doesn’t like the smell of her husband’s breath? Does she do so because she hears better out of one ear than the other and if she sleeps on her good ear she won’t be able to hear when her child cries out at night?

In my last novel, Matrimony, Julian meets his eventual-wife Mia after having spotted her in their college facebook. He dubs her Mia from Montreal. I wrote that phrase instinctively, probably because my own girlfriend freshman year of college was named Laura, and my roommate called her Laura from Larchmont. I liked the alliterative sound of those words.

Before I wrote Mia from Montreal, I had no idea where Mia came from. But she had to come from somewhere, and Montreal seemed as good a place as any. But then I had to own up to what I’d written. How did Mia’s family get to Montreal? Had they lived there for centuries? Were they expatriates, and if so, from where? And how did Mia end up back in the States, in western Massachusetts, for college?

I could have chosen Mia from Madagascar or Mia from Maryland, and if I’d chosen Mia from Maryland, there might have been, for all I know, a long section in Matrimony about her family’s tangled relationship with the clamming industry. But she wasn’t Mia from Maryland, she was Mia from Montreal, and so I discovered that her father had gone to teach physics at McGill, forcing her mother to abandon her career in the process, and that Mia, out of loyalty to her mother, decided to retrace her mother’s steps back to Massachusetts.

I knew none of this until I wrote the words Mia from Montreal, just as the writer who has a character who sleeps on her side doesn’t know why she sleeps on her side until she does so.

Q Noelle is the hardest character in the book to like (though we come to develop sympathy, maybe even affection, for her). How difficult is it to create characters that you know readers will find irritating? Do you dislike them as you write them?

As a writer, you have to love all your characters—not love them as human beings, certainly, but love them as characters, which means you have to take them seriously and respect their humanity and complexity. If you don’t, they won’t be real and you won’t be speaking the emotional truth. So while I could tell you that I’d rather go out to dinner with one than another, rather be stranded on a desert island with one than another, as characters, as my creations, they’re all equal; I play no favorites.

But that’s a different question from making your characters likable. This is one of the great myths of fiction writing—that characters have to be likable. Think of Flannery O’Connor’s short stories. There’s not a likable character in the bunch. But those are some of the most brilliant, most affecting stories around.

In fact, it seems to me that one of the pleasures of good fiction is that it allows us to enjoy the company of people on the page whose company we wouldn’t enjoy in real life. The writer’s obligation is to make his characters interesting, complicated, fully human, not to make them likable. A complicated, fully human, flesh-and-blood jerk is far preferable to a dull nice guy.

Q The book centers around Leo, who was killed before the book begins. Yet he gradually takes form and shape—to the point where he seems as developed as the others. Is it difficult to bring a dead character to life on the page when he can't speak for himself?

Leo is, in fact, the great hovering absence in the book, and the issue you’re pointing to gets at one of the challenges of writing a novel like this one—not just in terms of Leo but in general. In a book that takes place over seventy-two hours and that is so engaged with the past, you need to fold in a lot of flashback without slowing down the forward movement of the book.

That was probably the biggest aesthetic challenge I faced with this novel. In terms of Leo specifically—yes, it’s a challenge to bring a character to life who’s not there to speak for himself, but what I would say is that what this novel needs to do is less allow Leo to speak for himself than allow others to speak about him.

Because The World Without You isn’t about Leo—he’s dead. It’s about the family’s memories of Leo and their often contradictory interpretations of who he was, clouded as these interpretations are by grief and by different experiences of him when he was alive. That’s where my interest lies—not in Leo, but in how the rest of the family perceived him.

Q You've written elsewhere about a book's "theme," warning readers against looking for a central idea or lesson. Can you explain what you mean? If not a central idea, what do you hope your readers will come away after reading The World Without You?

Critics think in terms of theme; novelists don’t. A friend of mine in college wrote her psychology thesis on how adults group objects versus how kids group objects. Adults group the apple with the banana, and kids group the monkey with the banana. That’s a way of saying that kids are more natural storytellers than adults are, and it’s the writer’s job to teach herself to think like a child again, albeit like a smart, sophisticated child.

Critics are apple-banana people, and novelists are monkey-banana people. Which isn’t to say there aren’t themes in my novels, just that I don’t and can’t think about them as I write. I have to keep my eye on the prize, and the prize is my characters and my story. That’s what I’m focused on, nothing more and nothing less.

Q Let's talk about book clubs, of which I know you're a huge supporter. You wrote once that book clubs are smart...that they've offered insights into your work that has surprised you. Can you be more specific?

I’ve talked to so many book clubs that it’s hard to remember what I learned from whom, but I do think book clubs are incredibly valuable. I direct Brooklyn College’s fiction MFA program, so I spend a lot of my time with some of the most talented young writers around, and when I’m not spending time with them I’m spending time with my characters. It’s good to get out of my daily life, and out of my head.

I’m not in a book club because my life is a book club, and what I like about talking to book clubs is that you’re in a room with a dozen really smart people whose lives aren’t book clubs. These are just regular readers who take a day a month out of their busy lives to discuss your book, and it gives you a whole new perspective on what you’ve written, and so I’m incredibly grateful to them for that. Also, they’ve just read your book, so a lot of times they know your book better than you do!

Josh wrote a terrific guest blog piece for Books on the Brain back four years ago—about book clubs. It was so good that LitLovers devoted four separate articles on our own Blog to talk about it. Take some time to read them.... Here are the links

• Are Book Clubs Smarter Than Book Critics?

• So Where Are the Guys?

• How Do We Talk About Books?

• Are We All Reading the Same Books?

Also, be sure to check out Josh Henkin's website. There's fascinating video interview with Book Chase TV.

Site by BOOM

![]()

LitLovers © 2024