Just ♥ Words

They're off their game … unless maybe they've already thrown in the towel — because sometimes it feels like nobody's out there doing the dirty work, pulling in the perps. I'm talking about the Grammar Police.

They're off their game … unless maybe they've already thrown in the towel — because sometimes it feels like nobody's out there doing the dirty work, pulling in the perps. I'm talking about the Grammar Police.

Celebrities, politicians, pundits, authors, even the vaulted New York Times — all of them — are getting away with grammatical homicide.

This one came in today. It's subtle all right, but indicative of a downward slide into lawlessness. I count 2 "lock-em-ups" right off the bat. So let's read it and unpack it.

There's people that have been trying to line up for the opportunity.

1. THERE'S people

Oops: "people" is plural, so we say, "There are people" or "There're people." We don't say, "There is people" or "There's people."

- There're books in the library. — There's a book on the table.

- There're mice in the field. — There's a mouse in the house.

- There're lots of people. — There's a lot of people.

2. There's people THAT

Oops again: "people" are, well … people, and we use who when referring to homo sapiens. "That" or "which" refers to things.

- The person who gave me the book is my aunt.

- The aunt who gave me the book is my favorite.

- The people who read the book loved it.

- The ones who loved the book are my friends.

Both of these are common crimes. Pay attention and you'll start noticing how often you hear "there's" instead of "there're" … and "that" instead of "who."

Okay, then. Let's have another go at the sentence:

There're people who have been trying to line up for the opportunity.

Even better is this (try to avoid starting a sentence with "there"):

People have been trying to line up for the opportunity.

Let's face it, though: does any of it really matter? For me, it's like fingernails on a chalkboard, but in the larger scope of things … I'm not sure it does matter.

*Oops! Here's another one just in: "There’s help-wanted ads everywhere." —1/11/2018

Don’t do math (can’t). But do do grammar. (Notice I violated grammar here because I can. I'm so good…the grammar police always give me a pass.)

Don’t do math (can’t). But do do grammar. (Notice I violated grammar here because I can. I'm so good…the grammar police always give me a pass.)

I believe in grammar—its rules for clarity of expression—so others can make sense of what we try to say.

Nonetheless, there is one grammatical rule that needs to go: the "m" in the objective case of the pronoun "who" … that would be "whom."

That m is a nasty, pretentious little hold over from the days when Latin was the sine qua non (see "bees knees") of language.

It's along the same lines as that other silly rule about never ending a sentence with a preposition. And we all know what THAT led to: Winston's famous quip, "THIS IS SOMETHING UP WITH WHICH I WILL NOT PUT."

WHO WHOM—The test

THIS? — Give the award to WHOEVER deserves it.

Or this? — Give the award to WHOMEVER deserves it.THIS? — Give the award to those WHO you think deserve it.

Or this? — Give the award to those WHOM you think deserve it.

The who / whom imbroglio is overrated. Clarity can be achieved perfectly well without that niggling little letter. Who? Whom? Does it matter? We get the point.

The answers

Read at your own peril.Answer: Give the award to WHOEVER deserves it.

“Whomever” is not the prepositional object of “to.” Rather, WHOEVER is the subject of a dependent clause, “whoever deserves it.” The entire clause is the prepositional object. Phew!Answer: Give the award to those WHO you think deserve it.

“Whom” is not the object of “you think…whom.” “You think” is parenthetical…you can remove it altogether. So the “who” becomes a relative pronoun for “those” and the subject of the relative clause “who deserve it.”

See what I mean? So much ink spilled over a measly m!

The rules of grammar, in this particular case, are uselessly arcane. It's like being a guest at an EDITH WHARTON dinner party while you try to figure out THE OYSTER FORK… from the FISH FORK… from the SALAD FORK… from the DESSERT FORK. We all have better things to worry about.

So here’s my personal campaign for a better world: let's TRASH THE m in whom!

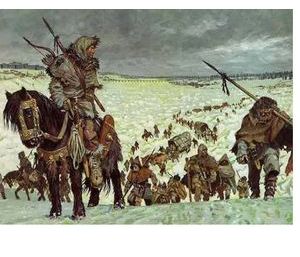

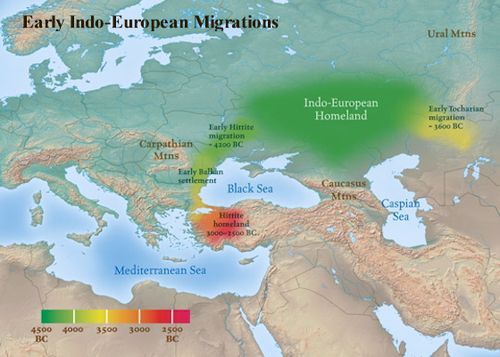

Oh, those feisty Indo-Europeans. Located some 4,000 years ago on the grassy steppes of Eurasia, just north of the Black and Caspian Seas, this ancient group of people gave us the English language—not just our language but nearly all of Europe's and India's, too.

Oh, those feisty Indo-Europeans. Located some 4,000 years ago on the grassy steppes of Eurasia, just north of the Black and Caspian Seas, this ancient group of people gave us the English language—not just our language but nearly all of Europe's and India's, too.

So how did the language of an isolated tribe of nomadic herders come to dominate so vast a territory? The answer is horses—and a human genetic mutation.

Map by Louis Henwood for The History of English Podcast

Horses were indigenous to the Eurasian grasslands, and the Indo-Europeans used them for meat—at first. But some bright (and brave) soul figured out that horses could be ridden and used for herding sheep and cattle. Once on horseback, the Indo-Europeans found they could raise and control larger and larger herds.

Another bright soul realized that instead of killing off so many goats or sheep for food, they could spare some and use their milk. Happily, that idea coincided with the spread of an errant gene—a mutation that produced lactase, the enzyme enabling humans to digest milk.

As a result, the herds thrived—as did the tribespeople, who grew in number and stature. The increase in herds and people gave way to the need for more land—and thus began the trek eastward to India and westward to Europe.

Map by Louis Henwood for The History of English Podcast

And if you were in their way? Well, they had horses—and you didn't—so you can guess who ended up with the land. Nonetheless, historians aren't sure how warrior-like the Indo-European tribes were, whether they always conquered or sometimes settled in peacefully. Most likely both.

However it happened, the Indo-Europeans came to dominate the inhabitants of their new lands. Their language continued to spread eastward and westward over thousands of years and thousands of miles, morphing into separate dialects...and eventually into separate languages, including the early Germanic languages, the ancestor of our own.

What this means, astonishingly, is that today about 50% of the world's population speak an Indo-European-derived language—3 billion of us—all from an ancient tribe of nomadic herders!

* This—and more, much more—is available on Kevin Stroud's wonderful podcast, The History of the English Podcast. Please take a week or two (or a month or two) to listen to his 50+ episodes. Stroud is a wonderfully lucid presenter and has put together a fascinating, detailed history of why our crazy language, English, is the way it is. If you love history and English, you'll be addicted. I am.

Also note the beautiful maps Stroud uses—two of which are included here. They were created for him by Louis Henwood. Thanks to both Kevin and Louis for their kind permission to use them.

Aah, look at Semiramis now—she's so much happier now that you've made a bit of progress in your mastery of the semicolon.

Aah, look at Semiramis now—she's so much happier now that you've made a bit of progress in your mastery of the semicolon.

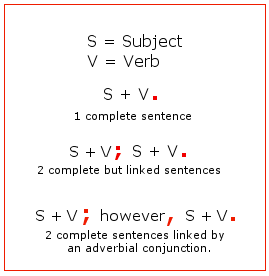

For a refresher scroll down to the previous post. Remember: the gist of the semicolon is that it connects two sentences without using a comma and a conjunction (and, but, or, so, for nor, yet).

In our final lesson, we're using semicolons with conjunctions—words like however, therefore, or nonetheless. They're called ADVERBIAL conjunctions.

—Semicolons & ADVERBIAL Conjunctions—Why use a semicolon?

Remember: a semicolon connects two related sentences.Think of it as a combination of a period and a comma. Notice the mark has one of each—top & bottom.

What's a conjunction?

A conjunction is a word that "conjoins," or links, two complete sentences. Regular conjunctions—and, but, so, for or, nor, yet—require a COMMA before the conjunction.Example: The dog barked , and the cat hissed.

Example: The dog barked , but the cat stood its ground.

Example: The dog barked , so the cat ran.What's an adverbial conjunction?

Like regular conjunctions, adverbial conjunctions link two full sentences—but with a SEMICOLON before and a COMMA after. They're "adverbs" in that they describe precisely how the 2nd sentence relates to the 1st—the same way adverbs describe verbs. Remember adverbs?—> She ate. How did she eat? She ate SLOWLY.

—> He sang. How did he sing? He sang LOUDLY.

Some common adverbial conjuctions

also however nevertheless anyway indeed nonetheless consequently instead now finally likewise otherwise further meanwhile then furthermore moreover therefore

Examples—

• It was too cold to enjoy the game ; however , she decided to go anyway.

The adverbial conjunction "however" indicates that the 2nd part of the sentence is in OPPOSITION to the first part. You could also use...nevertheless or nonetheless or still.

__________

• It was too cold to enjoy the game ; therefore , she decided not to go.

The adverbial conjunction "therefore" indicates that the 2nd part of the sentence is a CONSEQUENCE of the 1st part. You could also use...as a result or consequently.

__________

• It was too cold to enjoy the game ; furthermore , she didn't feel well.

The adverbial conjunction "furthermore" indicates that the 2nd part of the sentence is an ADDITION to the 1st part. You could also use...also or moreover.

__________

• It was too cold to enjoy the game ; instead , she went to the library.

The adverbial conjunction "instead" indicates that the 2nd part of the sentence is an ALTERNATIVE to the 1st part. You could also use...rather.

CAUTION

Don't confuse adverbial conjunctions when they're used as strict ADVERBS. Notice that in the following sentences they're offset by COMMAS. There's not a semicolon in sight.

• It was too cold, however, for the game.

• However, it was too cold for the game.

"However" functions as an ADVERB—not an adverbial conjunction—because there is only one sentence here (S + V): "It was"...

__________

• She did not, therefore, want to go to the game.

•Therefore, she did not want to go to the game.

"Therefore" functions as an ADVERB—not an adverbial conjunction—because there is only one sentence here (S + V): "She did (not) want"...

__________

• Furthermore, she did not feel well.

"Furthermore" functions as an ADVERB—not an adverbial conjunction—because there is only one sentence here (S + V): "She did (not) feel"...

Site by BOOM

![]()

LitLovers © 2024