Blogging & Musing...

One more addiction—this one's not on a plate or in a bottle but online. Pinterest: more fun than any one person should be allowed to have, but it's a great tool for book clubs. Move over, Facebook.

One more addiction—this one's not on a plate or in a bottle but online. Pinterest: more fun than any one person should be allowed to have, but it's a great tool for book clubs. Move over, Facebook.Pinterest is a social media site—it's an online "bulletin board" where you "pin" your favorite images from anywhere on the web, especially from other Pinterest users. Or you can pin images and photos you've already downloaded onto your computer. Pinterest does all the formatting for you. It's simple easy and devilishly clever.

Below is what a "bulletin board" looks like—a snapshot of LitLovers' board on Pinterest. Be sure to visit our real page—"Everthing Books" — to see the complete board. The Pinterest button on LitLovers home page (left-hand colum) will also take you there.

Why would book clubs use Pinterest? Because it's a great way to keep everyone up-to-date and to maintain a visual record of club activities. Your club can have its own page—and you can have as many "bulletin boards" on your club page as you want. You can add everything related to your book club...

- Add a "bulletin board" for the books you're reading—there's a space for captions (say, for titles or meeting date and locale).

- Add comments about each book. Any member can comment; it's just like Facebook.

- Add as many boards as you want—on the same page. Add a 2nd board for potential book ideas, a 3rd for club photos, and 4th for book-related recipes. Anything.

- Add boards for every member—on the same Pinterest page as your book club. Members can use their individual boards to "pin" everything...from the books they're reading on their own, to book-related gifts or personal photos.

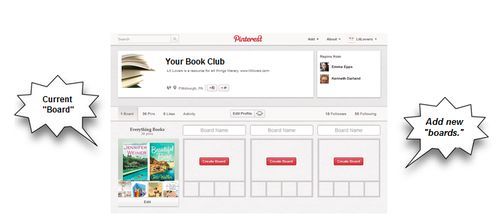

Take a look at a snapshot of a standard Pinterest page. You click on the empty gray boxes to add a new "bulletin board" and a title for your board. Then pin away.

It looks more complicated than it is. Believe me... if I can do it, you can do it. Head to the Pinterest Help page to get started. You'll find it under "About" in the upper-right corner. Follow the directions as best you can*...and "pin" to your heart's content.

Be warned, however. Once you get on Pinterest, you'll complsively click all over the place. You may not be able to get off.

* Call on a young person if you get stuck. They know everything.

Today's open letter from the American Library Association could have been a warning shot across the bow of U.S. publishers. But that's presuming the ALA could actually make good on its warning...which it can't. Libraries don't even have slingshots to use against publishing Goliaths.

Today's open letter from the American Library Association could have been a warning shot across the bow of U.S. publishers. But that's presuming the ALA could actually make good on its warning...which it can't. Libraries don't even have slingshots to use against publishing Goliaths.Still, it's a smart move—using an open letter to turn the spotlight on three of the country's (world's) largest publishers, who refuse to sell ebooks to libraries. The ALA's letter puts it this way...

Simon & Schuster, Macmillan, and Penguin have been denying access to their ebooks for our nation’s 112,000 libraries and roughly 169 million public library users.... The Glass Castle [ebook is] not available in libraries because libraries cannot purchase [it] at any price. Today’s teens also will not find the digital copy of Judy Blume’s seminal Forever, nor today’s blockbuster Hunger Games series —September 24, 2012

Not all publishers refuse to sell to libraries, as the ALA points out. However, without those three major players, ...

If our libraries’ digital bookshelves mirrored the New York Times fiction bestseller list, we would be missing half of our collection any given week due to these publishers’ policies. [ALA's emphasis.]This week, however, publishers and the ALA are meeting to try to iron out their differences—a hopeful sign, given that talks back in January of this year (2012) reached a stalemate...or worse. Penguin pulled out of library ebook sales altogether.

Random House, on the other hand, stuck around...but nearly tripled its prices to libraries, and Hachette's will more than double. HarperCollins limits libraries to lending its e-books only 26 times. This is according to Publishers Weekly.

But it's not like publishers are the bad guys. They are businesses...and must make money to survive. So stay tuned for another exciting installment in our suspense series—Libraries in the Digital Age.

See both Whither Go Libraries in the Digital Age articles—Part 1 and Part 3

Joshua Henkin is one of my favorite writers: his 2008 novel, Matrimony, was chosen as a NY Times Notable Book and reviewed here four years ago. His newest novel, The World Without You (2012) has received stellar reviews—phrases like "subtle and ingenious," "blazingly alive...a living, breathing world," "powerful and unexpected...compassionate and beguiling." See LitLovers Book Review.

Joshua Henkin is one of my favorite writers: his 2008 novel, Matrimony, was chosen as a NY Times Notable Book and reviewed here four years ago. His newest novel, The World Without You (2012) has received stellar reviews—phrases like "subtle and ingenious," "blazingly alive...a living, breathing world," "powerful and unexpected...compassionate and beguiling." See LitLovers Book Review.From my keyboard to your eyes—READ THIS BOOK! It's the story of a family that gathers a year after their son and brother Leo was kidnapped and killed in Iraq. Parents, siblings, and Leo's widow meet in remembrance and grief...as they struggle to live in a world without him.

Joshua has generously "stopped by" to answer some questions about his newest novel, and LitLovers is delighted to welcome him.

Q Not a lot happens in The World Without You in terms of plot—though a good deal does happen among characters. You seem to prefer character-driven over plot-driven stories. Why is that?

You’re not the first person to say that not a lot happens in The World Without You in terms of plot, and while I understand what you’re saying, I disagree. A son has been killed in the Iraq War. His parents are splitting up from the grief. His widow has a new boyfriend. There’s a lot of plot there.

That said, I think you’re fundamentally right, in that my fiction is always less concerned with what happens than with the characters who act and are acted upon. I think plot is important for fiction (you are, after all, telling a story, and a writer should never forget that), but the greatest plot in the world won’t be of interest to the reader if the characters don’t come alive on the page.

To me, fiction is first and foremost about characters. I want my readers to feel at the end of my book that they know my characters as well as or better than they know the people in their own lives. If I’ve done that, then I’ve succeeded.

Q The characters in The World Without You are beautifully realized—each clearly delineated from the others. How do you invent them—all the grainy details of their personalities and behavior? Do you find yourself, say, brushing your teeth...when an idea jumps out at you? Do you deliberate? Do you hold conversations with them? Do the characters ever take over? How does the miracle occur?

The miracle occurs slowly over time. You live with your characters day in and day out for years, and eventually they come to be fully formed. Who is your character? the writer should ask. Where did she grow up? What kind of work does she do? Does she like spinach? Does she sleep on her back, her stomach, or her side? It may seem inconsequential to know (much less describe) how a character sleeps, but not if the gesture is laden with meaning, as all gestures in fiction should be. Does the character who sleeps on her side do so because she doesn’t like the smell of her husband’s breath? Does she do so because she hears better out of one ear than the other and if she sleeps on her good ear she won’t be able to hear when her child cries out at night?

In my last novel, Matrimony, Julian meets his eventual-wife Mia after having spotted her in their college facebook. He dubs her Mia from Montreal. I wrote that phrase instinctively, probably because my own girlfriend freshman year of college was named Laura, and my roommate called her Laura from Larchmont. I liked the alliterative sound of those words.

Before I wrote Mia from Montreal, I had no idea where Mia came from. But she had to come from somewhere, and Montreal seemed as good a place as any. But then I had to own up to what I’d written. How did Mia’s family get to Montreal? Had they lived there for centuries? Were they expatriates, and if so, from where? And how did Mia end up back in the States, in western Massachusetts, for college?

I could have chosen Mia from Madagascar or Mia from Maryland, and if I’d chosen Mia from Maryland, there might have been, for all I know, a long section in Matrimony about her family’s tangled relationship with the clamming industry. But she wasn’t Mia from Maryland, she was Mia from Montreal, and so I discovered that her father had gone to teach physics at McGill, forcing her mother to abandon her career in the process, and that Mia, out of loyalty to her mother, decided to retrace her mother’s steps back to Massachusetts.

I knew none of this until I wrote the words Mia from Montreal, just as the writer who has a character who sleeps on her side doesn’t know why she sleeps on her side until she does so.

Q Noelle is the hardest character in the book to like (though we come to develop sympathy, maybe even affection, for her). How difficult is it to create characters that you know readers will find irritating? Do you dislike them as you write them?

As a writer, you have to love all your characters—not love them as human beings, certainly, but love them as characters, which means you have to take them seriously and respect their humanity and complexity. If you don’t, they won’t be real and you won’t be speaking the emotional truth. So while I could tell you that I’d rather go out to dinner with one than another, rather be stranded on a desert island with one than another, as characters, as my creations, they’re all equal; I play no favorites.

But that’s a different question from making your characters likable. This is one of the great myths of fiction writing—that characters have to be likable. Think of Flannery O’Connor’s short stories. There’s not a likable character in the bunch. But those are some of the most brilliant, most affecting stories around.

In fact, it seems to me that one of the pleasures of good fiction is that it allows us to enjoy the company of people on the page whose company we wouldn’t enjoy in real life. The writer’s obligation is to make his characters interesting, complicated, fully human, not to make them likable. A complicated, fully human, flesh-and-blood jerk is far preferable to a dull nice guy.

Q The book centers around Leo, who was killed before the book begins. Yet he gradually takes form and shape—to the point where he seems as developed as the others. Is it difficult to bring a dead character to life on the page when he can't speak for himself?

Leo is, in fact, the great hovering absence in the book, and the issue you’re pointing to gets at one of the challenges of writing a novel like this one—not just in terms of Leo but in general. In a book that takes place over seventy-two hours and that is so engaged with the past, you need to fold in a lot of flashback without slowing down the forward movement of the book.

That was probably the biggest aesthetic challenge I faced with this novel. In terms of Leo specifically—yes, it’s a challenge to bring a character to life who’s not there to speak for himself, but what I would say is that what this novel needs to do is less allow Leo to speak for himself than allow others to speak about him.

Because The World Without You isn’t about Leo—he’s dead. It’s about the family’s memories of Leo and their often contradictory interpretations of who he was, clouded as these interpretations are by grief and by different experiences of him when he was alive. That’s where my interest lies—not in Leo, but in how the rest of the family perceived him.

Q You've written elsewhere about a book's "theme," warning readers against looking for a central idea or lesson. Can you explain what you mean? If not a central idea, what do you hope your readers will come away after reading The World Without You?

Critics think in terms of theme; novelists don’t. A friend of mine in college wrote her psychology thesis on how adults group objects versus how kids group objects. Adults group the apple with the banana, and kids group the monkey with the banana. That’s a way of saying that kids are more natural storytellers than adults are, and it’s the writer’s job to teach herself to think like a child again, albeit like a smart, sophisticated child.

Critics are apple-banana people, and novelists are monkey-banana people. Which isn’t to say there aren’t themes in my novels, just that I don’t and can’t think about them as I write. I have to keep my eye on the prize, and the prize is my characters and my story. That’s what I’m focused on, nothing more and nothing less.

Q Let's talk about book clubs, of which I know you're a huge supporter. You wrote once that book clubs are smart...that they've offered insights into your work that has surprised you. Can you be more specific?

I’ve talked to so many book clubs that it’s hard to remember what I learned from whom, but I do think book clubs are incredibly valuable. I direct Brooklyn College’s fiction MFA program, so I spend a lot of my time with some of the most talented young writers around, and when I’m not spending time with them I’m spending time with my characters. It’s good to get out of my daily life, and out of my head.

I’m not in a book club because my life is a book club, and what I like about talking to book clubs is that you’re in a room with a dozen really smart people whose lives aren’t book clubs. These are just regular readers who take a day a month out of their busy lives to discuss your book, and it gives you a whole new perspective on what you’ve written, and so I’m incredibly grateful to them for that. Also, they’ve just read your book, so a lot of times they know your book better than you do!

Josh wrote a terrific guest blog piece for Books on the Brain back four years ago—about book clubs. It was so good that LitLovers devoted four separate articles on our own Blog to talk about it. Take some time to read them.... Here are the links

• Are Book Clubs Smarter Than Book Critics?

• So Where Are the Guys?

• How Do We Talk About Books?

• Are We All Reading the Same Books?

Also, be sure to check out Josh Henkin's website. There's fascinating video interview with Book Chase TV.

In a previous blog post, we asked whether bookstores will go the way of dinosaurs? The question is even more pressing for libraries, which face a brave new digital world...on top of state and local budget cuts.

First things first: how will libraries adapt to the growing e-book age? That question plagues both libraries and publishers as the trend to digital books shoots upward. More and more of us are turning to Kindles, Nooks, and tablets—we find a book and download it NOW! It feels so good.

But what happens when you download an e-book from the library? Do you have to stand in a virtual line for two weeks till it's your turn to download their single copy? If that's the case, bye-bye library...it's a straight shot to Amazon!

Libraries don't own e-books the same way they own book-books. They license them from publishers through distributors. So...how many times are libraries allowed by publishers to lend the same e-book (simultaneously and over time)? Only once...20 times...100...1,000 times?

Fortunately, libraries and publishers are working on a business model that will sustain them both. They may settle on a subscription fee...or a flat fee per e-book, but whatever the ultimate solution, it should allow both to survive and thrive. At least in the near term.

The long-term is murkier: are bricks & mortar libraries even necessary? If books are virtual, existing in some amorphous computing cloud, will we need never-ending rows of bookshelves? If research is done by computers, what role will reference librarians play? We can deal with those questions in another blog post. But for now, let's say that very smart people are putting their heads together on this issue, too.

The final question—budget cuts. I've got a four-letter response to that...but it's unprintable.

Here's the four-word response—change our tax system.

If we're worried about dumbing down the American mind, something's very wrong with our priorities when we reduce library funding. The world may be turning digital, but for now—and for some time in the future—libraries serve as the communal repository of knowledge...available to all comers.

See the follow-up articles: Whither Go Libraries in the Digital Age—Part 2 and Part 3.

Are local bookstores today's literary dinosaurs? A lot of people think so...and think Amazon has all but ensured their extinction

Are local bookstores today's literary dinosaurs? A lot of people think so...and think Amazon has all but ensured their extinction

Author Richard Russo unwittingly kicked off a kerfluffle by penning a NY Times op-ed piece. He, along with some big-ticket authors (Stephen King, Ann Patchett, and Anita Shreve and others), bemoaned the fate of brick & mortar stores. For Patchett bookstores represent "a critical part of our culture." Same with Tom Perrotta, who called them part of a "vital, real-life literary culture.” What's controversial about that?

Well, hold on: a couple of days later, online Slate magazine's Farhad Manjoo weighed in, calling Russo & company's argument "bogus." Pulling no punches, here's what he said:

Russo hangs his tirade on some of the least efficient, least user-friendly, and most mistakenly mythologized local establishments you can find: independent bookstores. Russo and his novelist friends take for granted that sustaining these cultish, moldering institutions is the only way to foster a “real-life literary culture,” as writer Tom Perrotta puts it.

Ouch! That hurts. Catch the words "least user-friendly" and "cultish, moldering institutions"—bookstores, for heaven's sake! But Manjoo makes an interesting case: because of online's low prices, ease of ordering, and instant access through digital readers, people are actually reading MORE. That's real-life literary culture, he says.

As far as preserving local community culture, here's what Manjoo has to say about that:

If you’re spending extra on books at your local indie, you’ve got less money to spend on everything else—including on authentically local cultural experiences...[your] local theater company...city’s museum...locally crafted furniture.... Each of these is a cultural experience that’s created in your community. Buying Steve Jobs at a store down the street isn’t.

My smart husband Pete says that Manjoo's own argument is bogus. It's not buying books that provides a cultural experience. Russo and others are referring to the store itself—a place to gather, real people to talk to, books to touch, chairs to sit on, a friendly storefront that graces a local street.

The issue won't go away; it resurfaced the other day on NPR (6 months after Russo's NY Times piece). The announcer interviewed Manjoo and a local bookstore owner, who sadly couldn't seem to address any of Manjoo's points. All of which allows to ME to pontificate...

Who's right or wrong? It doesn't matter. The fact is that local bookstores are bordering on extinction. It. Will. Happen...at some point. The younger generation was rasied on techno-pablum; they don't get all dewey eyed over books like we do. They get their news online...play games online...connect with friends online...look up words online.... They LIVE online. It's what they've grown up with.

Bye-bye bookstores. Will we miss them? You bet—big time! Will it alter our reading habits or our literary experience? Probably not. Still, it will be a different world, and we'll all have to adjust—I don't think we'll have a choice. Sigh....

Some years ago, when her daughter entered the fourth grade, author Tracy Carbone* became part of a Mother Daughter Book Club. I asked Tracy to share some ideas with the rest of us on how to go about starting a club for moms and their girls. So...here's Tracy!

Some years ago, when her daughter entered the fourth grade, author Tracy Carbone* became part of a Mother Daughter Book Club. I asked Tracy to share some ideas with the rest of us on how to go about starting a club for moms and their girls. So...here's Tracy!

A beautiful, poignant story, Tracy. Thanks so much for sharing it. If anyone else has been part of a mother-daughter book club...let us hear from you.Mother Daughter Book Club

Tracy L. CarboneNine years ago Lisa, the mother of one of my daughter's friends, learned she had breast cancer. Fortunately, she survived. Two years later she decided she wanted to do something special—something to create lasting memories for her oldest daughter.

So Lisa made some calls to find out who would be interested in starting a Mother Daughter Book Club. Ten of us signed on—five mothers and five daughters—all of us excited to be in such an exclusive group.

One of the first things Lisa did was to create a binder, which we used month after month...year after year. In it were the names of each month’s book, along with the five discussion questions posed by the daughter who ran that month’s meeting. Whoever ran the meeting got to host the group and choose the book for the following month. Our first book was the beloved 1945 children's classic—The Hundred Dresses by Eleanor Estes.

By the end of the girls' fourth grade year, we had read one book a month, most of them tame and friendly. But one question kept popping up, time and again: as our girls read the books and studied the plots they always asked, “Why don’t the characters just tell their parents?” We moms wondered the same thing, and their question revealed to us just how strong our bonds were with our daughters—and how our club had become a place where they could trust us.

With each book, we mothers were reminded of our own childhoods, often sharing with the group and our daughters stories no one had heard before. By the end of nearly every meeting, there were tears of joy and remembering, and heaps of sharing.

The girls matured, moving into fifth, sixth and then seventh grades. When bras and periods came into play, we moved up to books like Are You There God? It’s Me Margaret (Judy Bloom, 1970). We also combined movies with books if possible, including Because of Winn Dixie (Kate DiCamillo, 2000) and The Last Song (Nicholas Sparks, 2009), as the girls grew older.

Sadly, midway through the girls' seventh grade, Lisa’s cancer returned with a vengeance. We stepped up the meetings, choosing riskier books, teaching our girls as much about love and heartbreak and reality as we could, preparing them for the road ahead in an environment—our club—where they could feel safe.

Books like So B. It (Sarah Weeks, 2004), Jars of Glass (Brad Barkley, 2008), Hope Was Here (Joan Bauer, 2000) and Call Me Hope (Gretchen Olson, 2007) filled our shelves. These were life-affirming stories that demonstrated tenacious female characters finding strength in what remained. We read Mother-Daughter Book Club (Heather Vogel Frederick, 2007) and set up a conference call with the author, while luxuriating in an oceanfront hotel in Maine.

The five girls grew very close because of this bond. Lisa lost the battle to cancer at the beginning of the girls’ eighth grade. Though the bookclub carried on the rest of the year, by high school, the girls’ workloads were heavy and extra reading wasn’t possible.

We had a good clip though. Five years of stories of courage and love and life. I wouldn’t trade those memories for anything.

* Tracy L. Carbone is author of The Soul Collector for young readers. Check out her book on Amazon (click on the book's cover image). Also, be sure to visit her website at Tracy L. Carbone's Writing Website.

Now we know why we're hung up on reading. We talk about the guilty pleasures of the novel, of being sucked into a story, but it turns out we have an excuse. Lucky us—we're actually hard wired to respond to fiction.

Now we know why we're hung up on reading. We talk about the guilty pleasures of the novel, of being sucked into a story, but it turns out we have an excuse. Lucky us—we're actually hard wired to respond to fiction.

If a character in a book walks across a room to close a window, the brain's motor cortex—the part that directs our physical action—lights up. It's as if we, not the character, got up out of our chair to close the window. More suprising, the motor cortex region associated with leg movement and another with arm movement both light up.

But wait! There's more! When scents or textures are described, our brain's olfactory and sensory regions kick in. So "her skin was smooth as silk" elicits a more powerful brain response than "she had lovely skin." High-five for metaphors.

We've long intuited that literature allows us to transcend our own skin (speaking of skin) and experience, from the inside out, how someone else views the world. And guess what...brain studies confirm it.

It turns out people who read are more empathetic, with a higher proclivity for understanding different viewpoints. This cause-and-effect relationship holds true even when taking into account that people who empathize might be more inclined to read than those who don't.

Be sure to read the fascinating article by Annie Murphy Paul: New York Times, March 12, 2012. It's good reading...will light up your brain!

Site by BOOM

![]()

LitLovers © 2024